When rock and roll first became popular, some performers who had already established themselves in other genres had to walk a fine line between capitalizing on the fad and alienating existing fans. Several records by women from this era show that one technique to strike this balance was to perform songs that juxtaposed rock and roll with another genre. Often, the verse will be in one style and the chorus in the other. These songs typically also have an element of humor—we get the sense that the performer is making fun of one genre or the other—but there may be some ambiguity in the end as to the performer’s “real” style.

Three songs, all popular between 1955 and 1956, demonstrate how this works.

One example is Wanda Jackson‘s recording of “I Gotta Know.” In her autobiography, Jackson writes:

“I told [songwriter Thelma Blackmon] about Elvis encouraging me to try my hand at rockabilly music, but I confessed that I didn’t really know how to get into it. I had a dilemma because I wanted to venture into a new realm, but I also didn’t want to lose my country fan base. Unbeknownst to me, Thelma took it upon herself to go off and write a song that blended the two styles together. When she brought me “I Gotta Know,” I said “This is it!” 1

Here’s Jackson discussing and performing the song live in a 2018 performance (audio courtesy of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame):

Successful performance of the song relies on the arrangement and performance style creating an obvious contrast between the two sections. Here, the choruses—which in Jackson’s 1956 recording feature fiddles and pedal steel—resemble those of a country ballad, and Jackson plays up the twang in her voice. The verses, on the other hand, become faster and more percussion-heavy, and Jackson turns on her signature rockabilly growl. The record became one of her more popular singles that year.

Another example of this kind of musical switching occurs in Teresa Brewer’s recording of “Sweet Old Fashioned Girl,” also from 1956, which became a top 10 hit in Billboard. Brewer started her career as a pop singer in the late 1940s. She was a versatile vocalist, and she did participate in the practice of covering R&B songs for major labels, but neither she nor her record label ever went all in on marketing her music as rock and roll. “Sweet Old Fashioned Girl,” however, plays with the idea that she could have.

Accompanied by orchestral strings, Brewer asks “wouldn’t anyone like to meet a sweet old fashioned girl?” and then scat-sings a silly tune. Moments later, the strings abruptly cut out in favor of a jump-blues inspired band, and Brewer sings: “Who’s a frantic little bopper in some sloppy socks / Just a crazy rock and roller, little Goldilocks.”

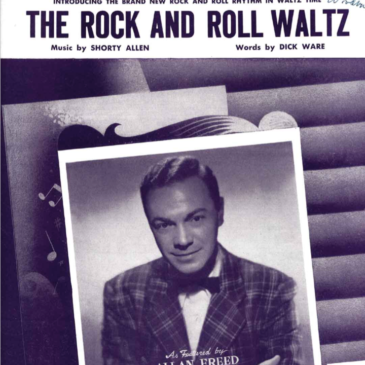

Kay Starr’s recording of “Rock and Roll Waltz” also fits this model. The idea for the song started with Alan Freed:

Songwriters Shorty Allen and Roy Alfred, always turning over new song ideas, were tuned into Alan Freed’s Rock ’n Roll Show one day, when the famous jockey happened to remark in connection with a record he was about to play, “The next thing we’ll have is rock and roll in waltz time.” That was all the fellows needed. They wrote the tune, the first rock ’n roller in that tempo in history, and based the lyrics on some of the romantic thoughts expressed in the many wires and letters received by Freed.2

Much of the record is a lilting waltz, with orchestral strings and in a clear 3/4 time. Over this, Starr tells the story of a young teen who happens upon her parents trying to dance to a rock and roll record. But twice within the song, when Starr pronounces the phrase “one, two, and three rock / one, two, and three roll,” she changes her vocal timbre to a gruffer sound, and the accompaniment correspondingly shifts to a brass band.

The song shot to #1 on the pop charts, where it remained for several weeks.

Rock and roll was still controversial at the time these three records were made, so these songs and their arrangements may have allowed some women singers—particularly white, middle-class women—to dabble in rock and roll in a non-threatening way.